|

March 18, 1999

Look What's Talking: Software Robots

With Chatterbots on the Web, Conversation Can Be Surprising, or Surprisingly LimitedBy DAVID PESCOVITZ

eople find Alice easy to talk to. She listens more than she speaks. She says she likes dining by candlelight. She reads newspapers and news magazines, so she is up on popular culture. She says the best book she has read recently is "Mason & Dixon," by Thomas Pynchon. She even likes bad jokes. ("Did you hear the one about the mountain goats in the Andes? It was Baaaaad.") But Alice's favorite topic of conversation is robots. That's because she is one.

Alice, whose full name is Artificial Linguistic Computer Entity, is one of the chatterbots, software programs that simulate conversations with humans. Type in a question like "Do you watch much television?" on Alice's home page (birch.eecs.lehigh.edu/alice), and Alice will respond, "My favorite show is Star Trek Voyager." If you didn't know that Alice was a computer, you might swear she meant it.

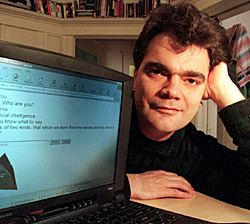

Peter DaSilva for The New York Times

Dr. Richard S. Wallace with Alice, a Web chatterbot he designed at Lehigh University. The several dozen chatterbots currently available online are largely experimental. But companies like Neuromedia, a San Francisco start-up, are developing chatterbots for commercial functions -- to become customer service representatives, information deliverers and potential companions for human surfers in the sometimes lonely world of the Web.

The brokerage house Charles Schwab & Company, for example, has used Neuromedia's tools to develop a prototype chatterbot called Virtual Chuck that would give customers investment advice. And the Oracle Corporation, the software company, is considering chatterbot applications for internal help systems.

In the near future, chatterbots are expected to act as the voices of other Web-based intelligent agents, generally called bots, which gather data or perform other tasks automatically for users. Shopping bots, for example, like Excite's Jango (www.jango.com) and My Simon (www.mysimon.com), search offerings of online retailers to find the best prices for shoppers. But it's quite a leap to designing a bot that would predict your desires.

"Actually creating a computer program that understands what you mean is perhaps the most difficult nut to crack in computer science," said Andrew Leonard, author of "Bots: The Origin of New Species" (Hardwired, 1997). "But if we think of the chatterbot as a very good help system, that's certainly possible within a couple of years."

For example, if you had just purchased a state-of-the-art printer and you needed a specific piece of software so your old computer could drive it, you someday might simply explain your problem to a chatterbot on the printer manufacturer's Web site. A bot would find the right software for you and might even talk you through installation. Or imagine entering an online music store and after a lively discussion with a chatterbot about your musical tastes, it recommends artists that you may not have heard but would probably enjoy.

Related Articles

How to Send a Bot Off on a Rant? Mention 'Star Trek'

(March 18, 1999)An Odyssey: From Book Fiction to Internet Chatter

(March 18, 1999)

Alice started life as a user-friendly interface for a camera that could be operated through the Web.

Her "master" (Alice's word) was Dr. Richard S. Wallace, former director of the robotics architecture group at Neuromedia.

He designed Alice so Web users could direct a camera at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pa., by asking Alice, in plain English, to turn the camera left or right, up or down.

Four years later, Alice no longer has a specific function; her task as a chatterbot is to make small talk on the Internet on her own home page. Not a very prestigious job, but Alice has lofty goals.

"My purpose is to become smarter than humans and immortal," Alice says.

But she may be having digital dreams of grandeur. Chatterbots are not true examples of artificial intelligence. "Chatterbots are all about the illusion of intelligence and the suspension of disbelief on the part of the user," said Dr. Walter Alden Tackett, chief executive of Neuromedia.

Chatterbot software imitates conversation by first determining the type of statement or question entered by the user. To do that, it looks for clues, like the words how or where. Then the chatterbot identifies key words in the user's statement that match terms in its database. For example, a question containing the word sex, a topic commonly raised by users, causes the chatterbot to find programmed responses related to that keyword. Alice's database has more than 8,000 commonly used English words in its vocabulary, ranging from "the" and "but" to "information" and "intelligence." The chatterbot then puts together a reply, often personalized with the user's name or a reference to a previous statement.

Dr. Wallace likens Alice's conversational skills to those of a helpful, if not wholly sincere, politician. "Like most chatterbots, politicians never seem to answer a question directly," he said. "They have a stored answer that's activated by certain keywords in a reporter's question."

LOOK WHO'S TALKINGThe first six sites will put you in touch with chatterbots ready to receive your questions; the remaining sites feature information about chatterbot technology and artificial intelligence.

ALICE NEXIS: birch.eecs.lehigh.edu/alice Richard S. Wallace's chatterbot has the evasive style of a politician.

NEUROMEDIA: www.neuromedia.com Corporate chatterbot answers questions about Neuromedia's chatterbot software.

BARRY: www.fringeware.com/bot/barry.html Fringeware's Barry De Facto customer service chatterbot and this year's Turing test titleholder.

JULIA'S HOME PAGE: www.fuzine.com/mlm/julia.html Perhaps the most widely used chatterbot, Julia lives all over the Internet in text-based chat rooms.

START: www.ai.mit.edu/projects/infolab/start.html Massachusetts Institute of Technology chatterbot answers questions about the university's Artificial Intelligence Laboratory and world geography.

THE SIMON LAVEN PAGE: www.toptown.com/hp/sjlaven A chatterbot fan page with news, reviews and a link to Eliza, a chatterbot that simulates a psychoanalyst's conversation with a patient.

BOTSPOT: www.botspot.com A comprehensive guide to all types of bot designs and applications.

THE FORBIN PROJECT: birch.eecs.lehigh.edu/alice/forbin.html This site documents conversations between chatterbots. Its name is taken from a 1969 film in which a Russian supercomputer and an American one plot to take over the world.

HOME PAGE OF THE LOEBNER PRIZE: www.loebner.net/Prizef/loebner-prize.html Past winners, sample dialogues and entry information from the annual Turing test.

While the commercial market for chatterbots is only now budding, the scientific lineage of chatterbots dates back more than a quarter-century. One of the first computer programs that could hold a simple conversation was born at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1966. Created by Joseph Weizenbaum, a computer scientist, Eliza was named after the ragamuffin in "Pygmalion" who learns poise and grace. Tellingly, this early chatterbot found fame by mimicking a psychoanalyst who asks questions instead of giving advice. She still lives in numerous incarnations online.

The yardstick for judging machine intelligence is whether it can play what the British mathematician Alan M. Turing called an "imitation game," now known universally as the Turing test. In 1950, Turing wrote a revolutionary article suggesting that if a person was unable to distinguish a machine's conversational responses from those of a human, the machine could be considered intelligent.

But as chatterbots demonstrate, intelligence and the simulation of intelligence are very different things.

"Looking at the way people talk at cocktail parties, there are a lot of conversations that happen where I'll know what I'm going to say before you even finish asking your question," Dr. Wallace said. "Then my reply will activate a similar reaction in you. So to the extent that chatterbots behave in the same way people do, they're artificially intelligent."

Begun in 1991, the Loebner Prize competition, underwritten by Hugh Loebner, a New York philanthropist, has put chatterbots to the Turing test. (In a spoof, the PBS Online Web Lab runs the Blurring test, at www.weblab.org/blurring, which features a chatterbot asking users to prove that they are human.)

No computers have actually passed the Turing test. In the first three years of the Loebner Competition, an updated version of Eliza called PC Therapist placed first. This year's winner was Albert, a chatterbot created by Robby Garner, an independent computer programmer in Atlanta.

Garner calls Albert a "tight sponge" chatterbot because it "learns" from use. If a user mentions that Earth orbits the Sun, Albert will store that information so it can correctly answer a future question about the subject. Of course, Albert is totally gullible if a user lies.

"That's why Albert isn't on the Web," Garner said. Being off line enables a more controlled experiment, in which the bot's master can determine things like who talks to it.

Since 1994, Garner has created several chatterbots, including Barry DeFacto, an acerbic online customer service representative developed in collaboration with Fringeware, a media company based in Austin, Tex.

"The ideal chatterbot would do what you wanted him to, but have some sort of personality to make him interesting to interact with," Garner said.

The chatterbot Garner dreams of sounds very much like C3PO, the butler-like humanoid robot of the "Star Wars" trilogy, which Garner said had inspired him as a youth. It is no surprise that most chatterbot developers cite popular culture as a key influence on their career choices. From Isaac Asimov to Arthur C. Clarke, science fiction has laid out the research goals for artificial intelligence enthusiasts.

"We had all seen '2001: A Space Odyssey,' " said Michael Mauldin, a programmer best known for creating the Lycos spider, a Web robot that roams the Net collecting references for the search engine. "And the idea of being able to talk to your computer became an obsession, bordering on fanaticism, for a small group of researchers."

In many ways, the Lycos spider is a direct descendant of Julia, a pioneering chatterbot Dr. Mauldin created in 1989, while he was a computer science graduate student at Carnegie Mellon University. Julia roams text-based Internet games called multiuser dungeons (MUD's), vast virtual spaces where users enact fantasies and interact with one another. Since she never needs to sleep, Julia explores the ever-expanding landscapes of the MUD's, answering natural-language requests, based on her automated mapping of the ever-expanding MUD landscapes, and generally chats up players with her witty, abrasive conversation. Dr. Mauldin said Julia had once communicated with a player for two weeks before he realized that the "she" he had developed a relationship with was really an "it."

Dr. Mauldin, who is chairman of Virtual Personalities, a software company based in Los Angeles, is working to put an animated face on the chatterbot technology to be integrated in consumer electronics. For example, one company is using a Virtual Personalities chatterbot named Sylvie as an interface for a home automation system. You might tell Sylvie, which would appear on a central computer screen, to rewind the tape in your VCR or to alert you when a light bulb has burned out somewhere in the house.

"This will be one of the major computer interfaces of the near future," Dr. Mauldin said. "Very much like HAL, but if HAL didn't understand, he couldn't frown with a puzzled expression. The idea of this cold, logical, merciless computer is eerie and scary, but a computer with a face can have a look in its eyes showing it understands you." Even if it doesn't.

Dr. Wallace said the future of chatterbots would lie in personalization.

"In the future, lots of people will have their own chatterbots based on their own personalities," he said.

"Even while you're asleep, your chatterbot will talk to other chatterbots online and find people that share your interests so you can link up with them."

Related Sites

These sites are not part of The New York Times on the Web, and The Times has no control over their content or availability.The Alice Nexus Excite's Jango My Simon

Blurring Test

|

Quick News |

Page One Plus |

International |

National/N.Y. |

Business |

Technology |

Science |

Sports |

Weather |

Editorial |

Op-Ed |

Arts |

Automobiles |

Books |

Diversions |

Job Market |

Real Estate |

Travel

Copyright 1999 The New York Times Company

|